Absolute Dating Problems

In archaeological terminology, there are two categories of dating methods: absolute and relative. Absolute dating utilizes one or more of a variety of chronometric techniques to produce a computed numerical age, typically with a standard error. Different researchers have applied a variety of absolute dating methods directly to petroglyphs or to sediments covering them, including AMS (accelerator mass spectrometry) radiocarbon, cation ratio, amino acid racemization, OSL (optically stimulated luminescence), lichenometry, micro-erosion and micro-stratification analysis of patina. (See http://home.vicnet.net.au/~auranet/date/web/index.html for a summary and references). These techniques have yielded mixed results in terms of reliability and feasibility, but, in any case, none has been applied to date in Saudi Arabia. It is hoped that absolute dating will be successfully implemented in the future in this region.

Another way that precise dating can be achieved is if the artist records the actual date of his or her creation, the name of a leader of known reign, or a distinctive historical event, like the inscription shown in the previous chapter about King Yousif Assar Yathar’s invasion of the Najran region in 518 CE. Then, however, it must be clear that the artist is referring to his or her own time, and not providing historical commentary.

Relative Dating of Rock Art

Given the current status of direct chronometric dating methods for Arabian petroglyphs, it is rare that the precise age of a rock art panel can be determined. However, all is not lost, and it is possible to establish a temporal sequence that can be quite edifying. To progress, it is essential to apply the second type, or relative, dating. The term refers to the fact that an approximate date can be inferred by comparison with something else of known age. In this case, a rock art panel may be judged to be younger, older or basically contemporaneous with another petroglyph, a site, an artifact, or other evidence of known antiquity. Relative dating, although somewhat less satisfying than absolute dating in terms of precision, is considerably more successful for petroglyphs.

Sometimes the proximity of a campsite or settlement that is dated directly by absolute dating methods is considered helpful for determining the age of an apparently associated petroglyph panel, but caution must be exercised, since it does not always mean that the site’s inhabitants were the artists who created the art. Often there are multiple sites of varying ages nearby and the petroglyph itself may be a palimpsest of images created through the ages.

On rare occasion, archaeological deposits can accumulate up against a petroglyph panel, concealing part or all of the art. In that case, it may be possible to discern a minimum age for the art because its creation had to precede the archaeological deposit covering it. This is not typical of the rock art in Saudi Arabia, however, which tends to be exposed and lacking any settlement or camp next to the cliff face.

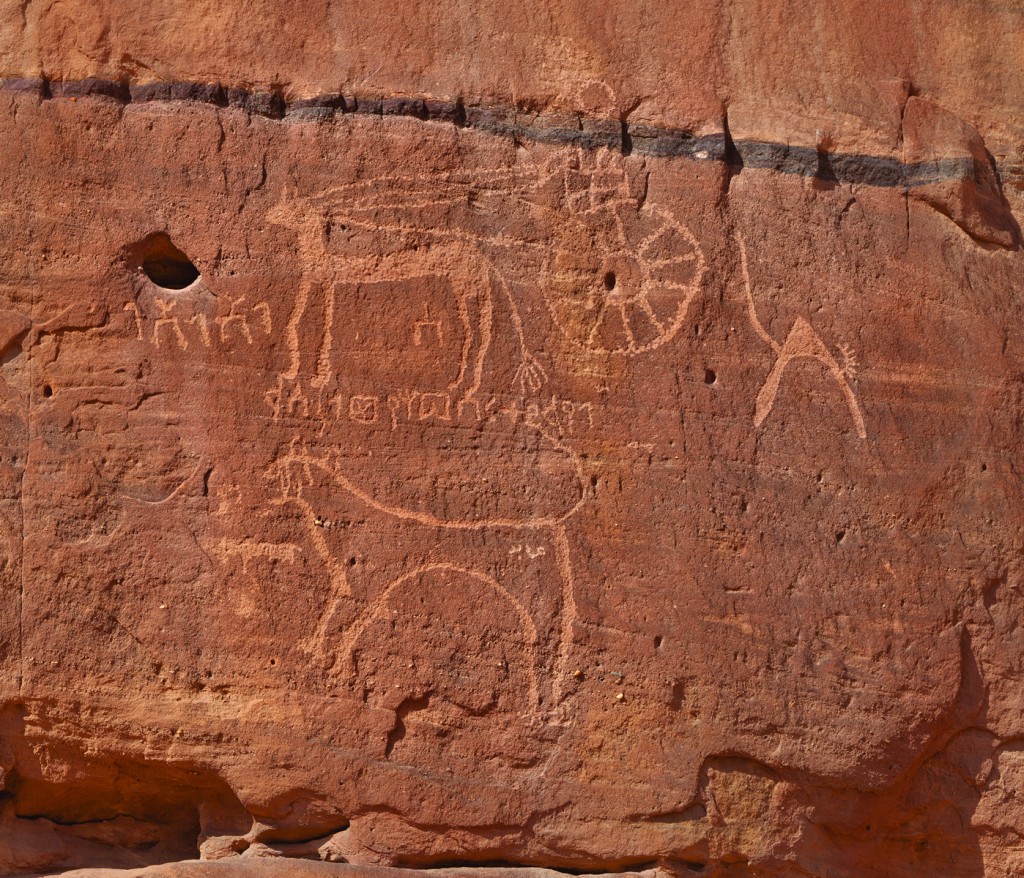

A palimpsest of animals from different ages at Shuwaymis: Faint images of Neolithic cattle, more recent camels and cavalryman, still younger men with exaggerated hands. The patina is darker on the older images and the newer images are brighter.

Although it is difficult to state the absolute ages of most of the rock art studied in this project, there are certainly general trends, best estimates and bracketing dates, which will be provided whenever possible. Clues to relative dating include: the manufacturing technique used; the patina covering the art; the layering of figures on top of each other; the style of human forms; and the particular animal species, types of artifacts and subject matter shown.

The Neolithic Cultures of the Holocene Wet Phase

For some 20,000 years, during the Late Pleistocene epoch (Ice Age), the Arabian Peninsula was overall very arid, as it is today. The earth at that time was considerably colder and the ice caps were much larger than they currently are. Many species, such as mammoth and woolly rhinoceros thrived in Eurasia and the mammoth, mastodon, camel and giant sloth lived in North America. Around 10,0000 BCE, a significant climate change occurred, altering environments, flora, and fauna in most parts of the world.

Following the Pleistocene, the Holocene or Recent epoch, witnessed a marked global warming that we still experience today. The climate was not stable, however, and around 7000 BCE, monsoon patterns shifted northward, causing the Arabian Peninsula to be more like a savanna than a desert. Rivers flowed, lakes formed, and the human inhabitants, flora and fauna embraced this lusher environment. The Holocene Wet Phase, as it is called, fluctuated greatly between humid and dry periods and then reverted to a more consistent arid condition around 3800 BCE, as the rain belt retreated southward (Parker et al. 2006).

The oldest known petroglyphs in Saudi Arabia are believed to date to the Neolithic period or Early Arabian Pastoral, which appears to coincide with at least part of the Holocene Wet Phase. These images are typically carved or pecked deeply into the rock surface. Compared to subsequent periods, the older Holocene Wet Phase Neolithic images usually have a patina that formed after the art and is evenly dispersed over both the images and the background. Later petroglyph artists took advantage of desert varnish, a dark, often shiny glaze that forms on rock surfaces in very arid environments. By scratching through the varnish and revealing the lighter colored underlying rock, it was possible to create bold images. Many of the rock outcrops bearing Neolithic images never developed dark desert varnish at all. The uniformly light color of the sandstone surfaces explains why the Neolithic artists had to incise or peck the images deeply into the rock: so that sunlight raking across them would cast shadows demarcating the outlines of the figures.

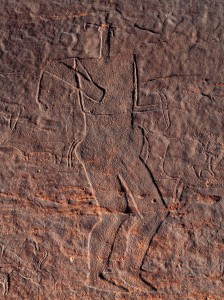

Larger than life figure of Neolithic hunter at Jubbah with his bow and bow case or quiver. A throwing stick protrudes from the case.

The most common Neolithic scenes are of hunter-herders with bows and arrows and throwing sticks, which are similar to a boomerang. The hunter is usually aided by a pack of hunting dogs. Although these people were part-time pastoralists with herds of sheep and goats, the art suggests that hunting played an important role in their subsistence. The relatively high frequency of hunting scenes in contrast to pastoral ones could also reflect the greater risk invested in hunting forays, and therefore perhaps more accompanying rituals. Wild species targeted as prey by Neolithic hunters included: now extinct large-horned wild cattle, onager, ibex, bezoar goat, oryx, addax, and gazelle. A Neolithic scene at Shuwaymis illustrates a confrontation with a lion, but such depictions are more common in later periods. The leopard and cheetah are also shown on Neolithic panels at Shuwaymis, but not with the frequency of prey animals.

At least in Ha’il Province, Neolithic bow-hunters were typically portrayed in a set style, with an elongated rectangular head lacking facial features, an angular ponytail or feather projecting from the top of the head, and a sheath in the pubic region, tied in back.

Toward the end of the Holocene Wet Phase, the Chalcolithic period (4th millennium BCE) replaced the Neolithic. At the site of Jubbah, in the northern province of Ha’il, some of the images may date to this somewhat later period. Fairly realistic female figures at Jubbah, possibly Chalcolithic in age, are elaborately clothed in ornate dresses with a sash cinching in the waist to highlight their physique. They also lack facial features, although their hairstyles are more clearly depicted than for the Neolithic men. The method of creating the figures is constant, with deeply carved outlines and little or no removal of patina. Their antiquity is supported by the absence of associated horses, camels, or writing.

Holocene Arid Phase

This petroglyph panel at Jabal Yatib was shallowly scratched through the dark desert varnish. The subjects (lion, palm trees, camels, horses, and writing), as well as the technique, indicate that it was done after the Holocene Wet Phase.

At the end of the Chalcolithic, the method of creating rock art shifted away from the laborious removal of large quantities of stone by making deep grooves and large recessed areas. After about 3800 BCE, when the Arabian Peninsula returned to extremely arid conditions, the rock surfaces in many areas started to form a dark brown to black desert varnish. These outcrops became the canvases of choice, since the removal of the thin veneer of desert varnish resulted in a high contrast between the subject and the background. Scratching through the thin surface patina revealed lighter-colored gold or pink sandstone beneath. The often dramatic images that resulted from this new technique highlight the outline or body of a figure by being lighter than the surrounding background. With this new method, the task of ancient artists was greatly facilitated, and they were able to create single figures or entire scenes relatively quickly. In contrast to the deeply incised Neolithic images, these shallower petroglyphs may fade more easily as patina gradually forms inside the subject area, rendering them less visible.

One of the chief subjects of research in this project was the response of animals and humans to the dramatic shift toward aridity after the Holocene Wet Phase. At the onset of the work it was hypothesized that the rock art might reveal significant changes in the frequencies of certain species, particularly medium to large wild herbivores. Unexpectedly, most of the prey animals and carnivores continued on in the rock art even with the return to an extremely arid climate. Only the wild cattle disappeared in petroglyphs and may have gone extinct in Arabia soon after the monsoon patterns shifted.

Otherwise, the biggest temporal change was the serial introduction of domestic livestock species. Distinctive domestic cattle with lyre-shaped horns and color patterns on their bodies appeared in the early part of the Arid Phase, after the wild cattle, their ancestor, vanished. It is likely that the images of early domestic cattle were produced in the 3rd-2nd millennia BCE since, based on patina on shared panels, they antedate cavalry, camels, and written text. As aridity increased, conditions would have gradually become less favorable for raising cattle in many areas. Still today, however, there are regions where cattle herding is feasible, especially those places that receive run-off from adjacent mountains or have a high water table and wells. The area around the modern city of Najran, in the southwestern part of Saudi Arabia, near the border with Yemen, is one such place.

The Late Bronze Age to early Iron Age is represented best by schematic images of chariots with a pair of four-spoked wheels, pulled by two horses. They are depicted in a fashion strikingly similar to the way artists showed them across Eurasia and North Africa, in aerial view, with the wheels lying flat and the horses in a recumbent position, either back to back or, more rarely, facing each other (MacDonald 2009). Although four-wheeled battlewagons and the peculiar two-wheeled straddle cars originated in Mesopotamia, the earliest actual two-wheeled chariots pulled by horses have been found in burial tumuli in Russia and Kazakhstan that date to around 1950-1750 BCE (Olsen 2010). It is therefore likely that the depictions in Saudi Arabia and North Africa are later, as this new innovation spread out from its source either in the Near East or the Eurasian steppe.

Chariot shown in profile at Al Sinya. Note the lion below, camel behind and associated ancient Arabic script.

Later, in the Arabian Peninsula, as elsewhere, heavy chariots with more than four spokes in their wheels and up to three passengers are shown in a new style. Replacing the earlier aerial view, they are now depicted in profile, like those in Mesopotamian temple art. These date to the first millennium BCE, with the likelihood that actual horses and chariots belonged to or were acquired as war booty from Assyrian, Neo-Babylonian or Persian armies.

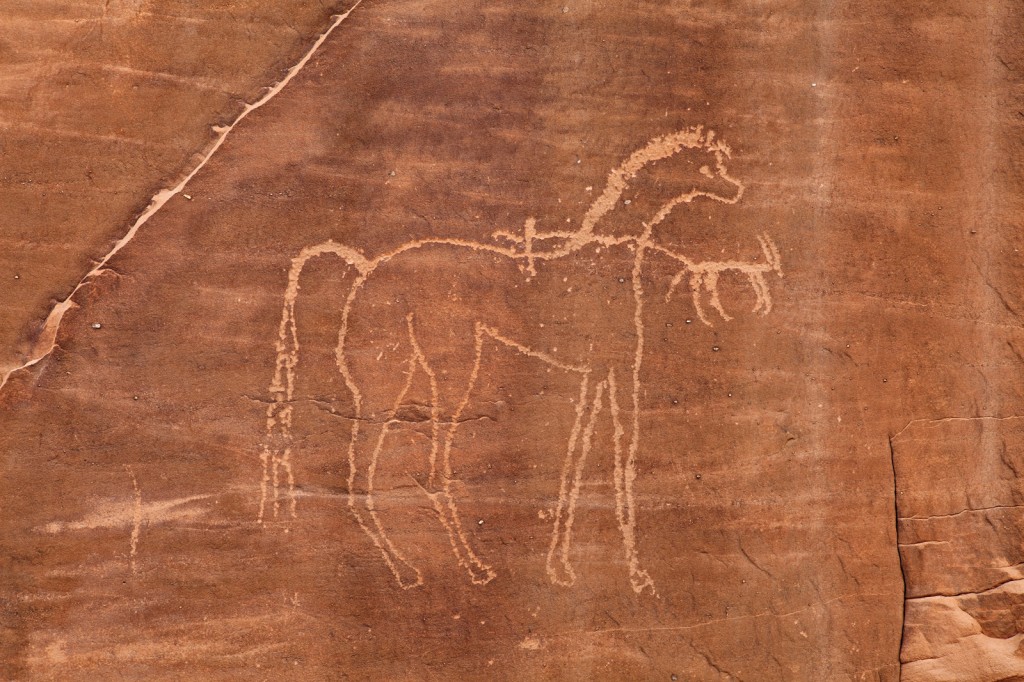

Horse at Jabala I, showing features of the Arabian breed. In this case, based on a slightly lighter patina, the diminutive rider and ibex appear to have been added later.

Horses with multiple features of the Arabian breed first appear in rock art in the northern part of Saudi Arabia. They are frequently accompanied by dromedary camels, as well as early Arabic script, such as Thamudic. The earliest firm date for Arabic writing (Thamudic B) also appears in the north, in the mid-sixth century BCE (MacDonald 2010:14). However, inscriptions similar to those found near Tayma (Tamanite) have been found in Iraq and are dated by archaeological context to the 7th century BCE (Winnett and Reed 1970:90). Thus, based on the associated writing, the earliest date we could comfortably assign to the Arabian horses is 7th-6th century BCE, unless and until evidence of earlier dates for writing is produced. The introduction of the Arabian horse breed in Egypt occurs in the New Kingdom, certainly by the time of Amenophis II (reign 1427-1401 BCE), if not earlier (Olsen 2010), most likely as war booty after successful engagement with Asian powers along the Levant. It would not be surprising, therefore, if evidence for Arabian horses that are contemporaneous with those of the Egyptian New Kingdom eventually emerges in Saudi Arabia.

It must be admitted that, as scientific evidence, artistic depictions are not on a par with actual skeletal remains of animals or real vehicles uncovered in excavations. Artists can return from distant lands where they witnessed foreign inventions or animals, or they can visually relate subjects that other individuals have seen elsewhere and described to them. Therefore, the artistic representations do not guarantee that the subjects depicted were actually present in that region. Also, artistic traditions can be tenacious, lasting decades or even centuries beyond an actual observation.

The Holocene Arid Phase, which continues today, led to a gradual shift in lifestyle and subsistence, from a nomadic life divided between hunting and herding to more full-time pastoralism. The arrival of domestic dromedary camels appears to have been a major contributing factor to this transition. As the oldest images of dromedaries are typically associated with Thamudic or other early inscriptions, the camel seems to have become significant only in the first millennium BCE. The earliest depictions of the distinctive breed of fat-tailed sheep also probably date to this period, particularly in the petroglyphs near Najran, in the southwest.

Still later, perhaps between the last half of the first millennium BCE and the first half of the first millennium CE, cavalry and battle scenes dominate petroglyphs. The most dramatic are to be found in the southwest, in Najran province, in a region known as Bi’r Hima. Also in this area, and in association with warriors, are female figures that have been interpreted as goddesses of fertility and war.

This temporal sequence is still in its preliminary stage of development and will undoubtedly be revised and supplemented as more information becomes available. However, it is already apparent that relative dating is extremely valuable and that it is often quite possible to place animal species and human activities in a sequence from early to late.